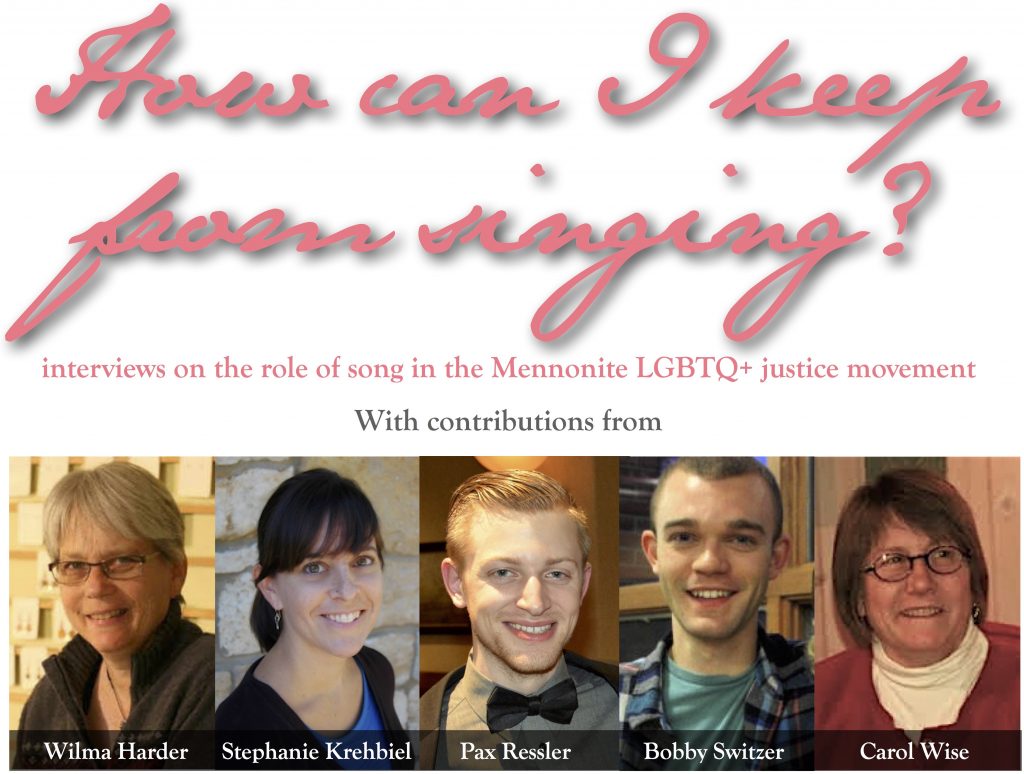

This series of posts shares interviews conducted by Bobby Switzer for a thesis project at Goshen College, curated for this series by Pax Ressler. The questions below are Bobby’s, with responses from Wilma Harder, Stephanie Krehbiel, Pax Ressler and Carol Wise. For more information about the Mennonite LGBTQ+ justice movement, see the appendix at the bottom of the page:

“A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel”.

Bobby Switzer: Has hymn singing been used strategically in the inclusion movement? If so, how?

Carol Wise: In the 90’s, there was a series of conferences sponsored by BMC referred to as the “Dancing Conferences.” Titles included Dancing at the Wall, Dancing at the Table, Dancing at the Water’s Edge, Dancing in the Southwinds, and one called Leading the Dance. These conferences were held at various places in the US and were important in bringing together lgbtq people and allies. Worship and music were important components of these conferences. Jane Ramseyer Miller (who has directed “One Voice Mixed Chorus” here in Minneapolis for 20 years) even wrote “Dancing at the Wall” for one of these conferences. I’ve attached a scanned copy of it. Within the Church of the Brethren, songwriter Lee Kranbuhl wrote a very catchy piece called “We are Not Going Away” that energized many people and was often sung.

It was Pink Menno who brought hymn sings into the inclusion movement with more passion. I think part of the ability of PM to do this was not only because of the giftedness of young musicians, but also because hymns could increasingly be sung and claimed with more power now that the church is at a different place because of the work that has been done over the decades. The power rather than simply the pain of the hymns and all that they represent in terms of community and faith can now be claimed more easily. I see this as a positive sign of genuine change. Music that once brought harm is now able to heal, at least to some extent. Sadly, the hymnology of the church remains problematic for many.

“Music that once brought harm is now able to heal, at least to some extent.” – CW

Pax Ressler: Hymn singing has been used both as a strategic and celebratory action for the LGBTQ+ justice movement in the Mennonite Church. LGBTQ+ leaders and those who operate in solidarity with them sing hymns (a “traditional” Mennonite practice) in denominational spaces as a subversive way of reframing common misconceptions of queer people as a “new, divisive problem” in the Church. Hymn singing is a celebratory way for queer people to empower themselves through song.

The spaces we often choose are unapologetically public; they are spaces that many people walk through or could hear singing from a distance. I think this action to boldly claim space is a powerful message to a Church that had yet to grant queer people any space. We often sing outside a delegate sessions where decisions are being made “about us, without us” or where opportunities to live into possibilities for a more just Church have been ignored or denied. We sing to respond to that silencing and powerlessness.

Stephanie Krehbiel: Definitely. The most obvious example is Pink Menno’s singing in the hallways and entrances at denominational meetings. And what gave that strategy particular impact was the way it was coupled with visibility, by means of everyone wearing pink. It has a really powerful spatial component as well; Pink Menno sings from the literal margins of official church events. At the same time, they’re often the only people at conventions singing the four-part harmony that is recognizably Mennonite for a lot of “ethnic” Mennonite folks. And Pink Menno tends to produce really good singing. Both of those factors are things that both add to their power and probably also limit their reach.

“Pink Menno sings from the literal margins of official church events.” – SK

There’s a significant overrepresentation of extremely skilled and gifted musicians in the queer, church-going Mennonite population. A lot of these folks got much of their musical training in Mennonite institutions and have been contributing music to their congregations for much of their lives. Not all queer Mennonites are musicians, obviously, but sometimes I wonder if musicians are more likely to stay with the church for longer, and thus they have a lot of impact on queer Mennonite activist strategy.

How were hymns chosen to be included in Pink Menno song books?

Pax Ressler: I developed a Pink Menno songbook for the 2013 Phoenix Convention and some of my priorities were: hymns in other languages and from other traditions (recognizing the intersectionality of oppressions that play out on the bodies of people of color, immigrants and queer people); hymns that we can easily sing together (familiar, in a singable range and can be done a cappella); hymns that avoid gender-driven language for God (though this is something we often have to change in practice, as opposed to on the page); hymns that celebrate our inherent goodness and worthiness (as opposed to the need for confession and calls to “righteousness”); hymns that musically “stir the spirit” (often with more soulful, African-American spiritual roots); hymns that can be sung and taught easily enough to put down our books and look up or clap; as well as a number of readings (relevant to LGBTQ+ justice) that could be used for Pink Menno/ BMC/Inclusive Pastor-led worship services and impromptu gatherings.

Hymns have often been chosen because of their content and subversive message to the fearful, homo/transphobic Church—but the way we deliver and sing hymns is also strategic. When I lead, I hope for the people gathered to access the joy and celebration of being together and raising our voices. If we can, we’ll sing from memory or using call and response—this allows us to look up and acknowledge passerbys in public, denominational spaces. The invitation is this: “Look into the face of a fellow sibling in Christ and ask yourself if God loves them any less than you.” The strategy is joy—to be a joyful, unrelenting singing presence and hope that our celebration is infectious.

“The strategy is joy—to be a joyful, unrelenting singing presence and hope that our celebration is infectious.” – PR

Has hymn singing helped to unify the movement?

Stephanie Krehbiel: Yes and no. I can’t imagine the movement without singing; it gives people something to meet over and to do when other forms of organizing and institutional transformation are at dead ends—and with Mennonites they are always at dead ends, because the institutions are so resistant to change. Singing allows people to imagine a kind of community that is at least somewhat independent of those power structures, and it feeds people spiritually, which can’t be underestimated. But music is also powerfully racialized, and in some ways that is its greatest limitation as a unifier in the Mennonite LGBTQ movement. Pink Menno hymn sings are a form of communal practice that is, for the most part, most accessible to people who grew up in white Mennonite churches, singing four-part harmony. Latino/a and African-American Mennonites often have evangelical, missionary worship practices with musical traditions that are much different from European and white U.S. Protestant hymns. That disconnect is a problem for Pink Menno in a denomination whose leadership is doing its best to pit the interests of queer people against the interests of people of color. I know Pink Menno leaders (some of whom are people of color) have lots of conversations about what the role of singing can or should be in future events, given this reality. My educated guess is that it will be less central to their strategy.

Has hymn singing been used to respond to power?

Wilma Harder: During the March on Washington we heard rumors that Fred Phelps and crew were demonstrating somewhere along the parade route. The BMC contingency decided to sing Amazing Grace to them as we walked by. I wouldn’t say they were power or authority, but the definitely were a presence. They seemed to actually listen, as we went by. Other than that, I don’t recall actively singing “at” someone, or a group of people, other than in a performance.

I produced and hosted a radio show for 25 years called A Women’s Circle. The intent was to get more airplay not only for women, but also for lesbians. The intent also was to bring into the listener’s conscience all the various -isms in the world simply by playing songs from various movements. I was not allowed to give my own opinions on air, but I was allowed to air just about any song that would bring to light some sort of injustice in the world. So I didn’t do much talking, but played lots and lots of music.

This show gave me, and many others, a voice. It was very powerful to those who felt minimized and unheard, and had a great following. There were so many songs, way too many to mention, that became anthems in the women’s music community. “Song of the Soul” (Cris Williamson) was one of them. Also “Singing for Our Lives” (Holly Near), “Testimony” (Ferron), “Ella’s Song” (Sweet Honey in the Rock) and “Gonna Keep On Walking Forward” (Judy Small) were all very well known and well sung in the lesbian community.

“This show gave me, and many others, a voice. It was very powerful to those who felt minimized and unheard.” – WH

Stephanie Krehbiel: Absolutely. In more ways than I could begin to quantify. The use of singing in Pink Menno actions has always had the dual purpose of sustaining the queer/ally community while at the same time responding to institutional exclusion and to conservative rejection/aggression. In a number of situations it has operated as a tool for diffusing acute conflict.

Appendix: A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel

Switzer: What do you know about the beginnings of the movement for inclusion in the Mennonite church? Were there notable moments of its origin? Specific actions that might mark its beginning?

Krehbiel: The most notable moment in the Mennonite movement for inclusion is probably the founding of Brethren Mennonite Council on LGBT Interests in 1976, by Martin Rock. (Back then it was “Gay and Lesbian Concerns.”) And that should be noted more broadly as an Anabaptist moment, since from the beginning it was ecumenical, with Brethren and Mennonites working together. Martin Rock was a gay man living in Washington, D. C. and he was fired from his position at Mennonite Central Committee for being gay after someone anonymously outed him. He had worked for them for 11 years. He started BMC around the same time that he was fired, with a group of gay Mennonite and Brethren men in the D.C. area. That organization grew (and diversified, at least in terms of gender), pretty steadily throughout the 1980s and 90s, and it continues to grow through its Supportive Communities Network.

Switzer: What have been the key moments/players in the church’s history with respect to LGBTQ+ inclusion?

Krehbiel: That’s a pretty hard question to answer because in a 40-year history, there have been a lot. BMC has been the central locus of LGBTQ Mennonite organizing for most of that history. In terms of what has happened within the institutional church—the (Old) Mennonite Church, the General Conference Mennonite Church, and eventually MCUSA—I’d say that very generally, the 1980s were marked by some gradual steps towards collective education (with many, many setbacks), the 1990s were a time of conservative retrenchment, and the MCUSA has been quite aggressively divided on LGBTQ inclusion from its inception. The MCUSA was essentially founded on a pact with conservative churches that openness towards LGBTQ inclusion would not be tolerated (see the 2001 Membership Guidelines). Conservatives interpreted that as law; moderates interpreted it as an “issue” that they hoped would become less consequential in time. LGBTQ Mennonites and those who supported them unconditionally were almost completely marginalized in the denomination’s founding. So the formation of MCUSA in 2001-2002 is certainly a key moment, and Mennonites are still living with the consequences of that.

It’s also important to remember that before MCUSA, the General Conference was certainly the more tolerant of the two denominations in terms of maintaining a congregational polity approach to churches that had LGBTQ members. That doesn’t mean there weren’t very homophobic voices within the denomination; it just means that GCs were less likely to expel congregations over LGBTQ members. The Old Mennonite Church had more of a bishop tradition as well as a stronger evangelical influence. Because so much of the General Conference was in Canada, the national split led to considerably fewer GC congregations than MC congregations in the new MCUSA. That has certainly had an effect on denominational politics.

The network of straight pastors who perform same-sex weddings has been increasingly active throughout the existence of MCUSA, particularly as queer couples have had more and more access to legal marriage. Jennifer Yoder and Luke Yoder formed Pink Menno in 2009 to be a visible queer presence at biennial MCUSA conventions and they have been the public face of the movement ever since.

Visit Part I

In the next “How can I keep from singing?” post:

- music to sustain the movement

- singing and social change

- lyrics and songs that have healed and hurt