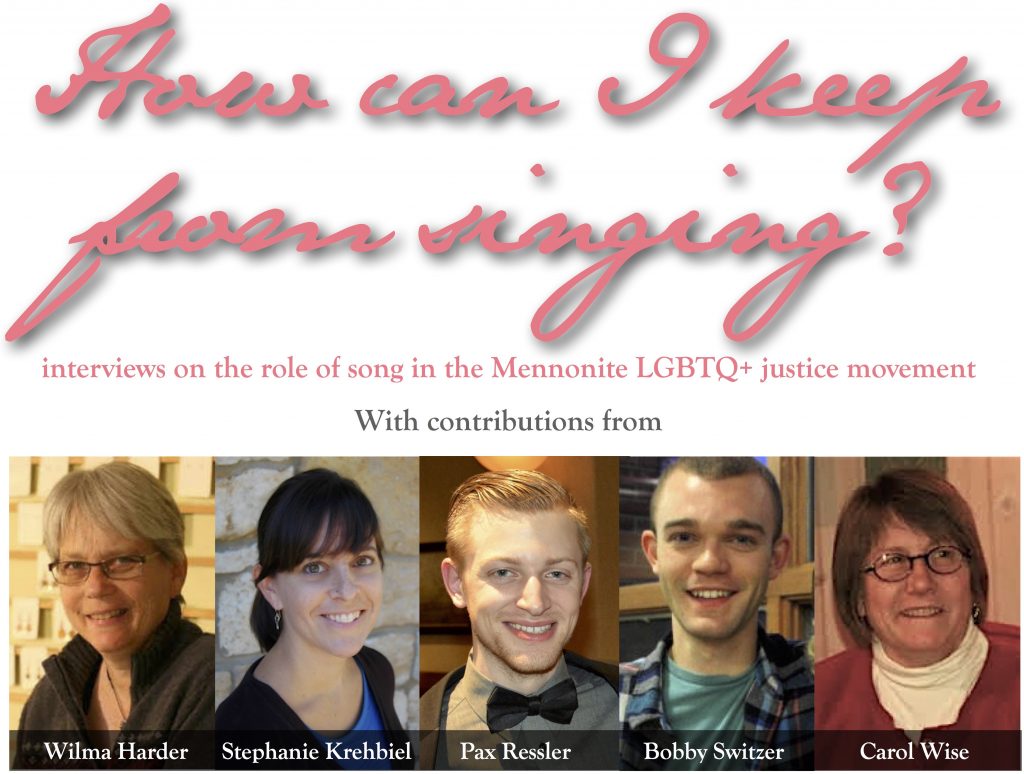

This series of posts shares interviews conducted by Bobby Switzer for a thesis project at Goshen College, curated for this series by Pax Ressler. The questions below are Bobby’s, with responses from Wilma Harder, Stephanie Krehbiel, Pax Ressler and Carol Wise. For more information about the Mennonite LGBTQ+ justice movement, see the appendix at the bottom of the page:

“A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel”.

Bobby Switzer: Why is hymn singing important to Mennonites?

Stephanie Krehbiel: That’s a mother of a question, isn’t it? I don’t have a particularly original answer. Mennonites have built a lot of their worship practices around getting rid of things: sacraments, aesthetic pleasures in worship, liturgy, ritual. Those eliminations have always had theological justifications. I think that’s part of how music has come to be so important. Of course, music is not separate from any of the sociocultural/political battles that have shaped the rest of Mennonite worship—all you have to do is look at the centuries-long conflicts over instruments in worship within Anabaptist groups to see that. Music is definitely a political arena. But it’s also the one place where a lot of Mennonites consistently seek spiritual nourishment and refuge, and that intensifies the desire to remove it from the realm of conflict and politics and make it into something “pure.”

“Music is definitely a political arena.” – SK

Carol Wise: Of course, music is essential to Mennonites. It has always been an important part of BMC conferences—often small groups offered various sacred pieces as part of the “entertainment” or for fundraising purposes. I recall many touching moments breaking into BMC events because of music. Music had an uncanny ability to remind people of the depth of their religious connections, even in exile from the church.

“Music had an uncanny ability to remind people of the depth of their religious connections, even in exile from the church.” – CW

What does hymn singing offer that is unique to social change? To the the inclusion movement? To Mennonites in particular?

Carol Wise: I would say that, like most social justice movements, music has played an important role in terms of providing encouragement, strength, connection and meaning. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement, however, the lgbtq movement did not emerge from Christian churches. Most would say that religion has tended to play a very negative role in the movement for lgbtq justice. One result of this was that songs that I think helped to provide a spiritual grounding for lgbtq people in the earlier stages of the movement did not come from hymns or the church. Rather, they came often from queer feminists such as Holly Near (“Singing for our Lives”), Carolyn McDade (“Spirit of Life), and Ronnie Gilbert.

Wilma Harder, there in Goshen, is the best person to go to for information about this—and Wilma has also provided strength to Mennonite lgbtq people through her music and life. The role of queer feminists and their music, including queer feminists like Wilma, is something that I hope you do not overlook in your paper.

Wilma Harder: First of all, I’m trying to think how I’d qualify the “Mennonite inclusion movement”. I guess I would include BMC Conventions/Gatherings/Retreats, and also specifically selected songs during a themed church service of inclusion. Also the songs BMC sang as a group as we marched together during the March on Washington (although that was asking for much wider inclusion than from Mennos, we certainly marched as Brethren and Mennonites).

I’m speaking of mostly 20-30 years ago. some of the songs we specifically picked to bring inclusion to the forefront, but I think mostly they were songs to say “We have been a part of the community all along. Why don’t you see that?”

Pax Ressler: Hymns offer a way for queer people and those who operate in solidarity with then to publicly “break the silence” of denominational oppression, process and “loving dialogue”. Hymn singing is something that many Mennonites do in times of struggle and hardship; singing is one of our responses to violence and oppression in our world—and in this case, our denomination. It’s prophetic.

Stephanie Krehbiel: I don’t know how well I can answer that. Music really offers up a site that is rich with contradiction. For Mennonites, some of the hymns that are most beloved are ones that have the most magisterial, patriarchal theology, and it’s interesting to see people’s varying levels of tolerance for that. Some people really have a need to change the words, because the words represent a systemic violation; some people seem to find some sort of pleasure in the almost embodied contradiction of singing a theology that they find repellent in a song they find aesthetically pleasurable. I see those negotiations happening even within a Pink Menno convention hymnsing.

I think the most dangerously simplistic thing you could do in writing about music and social change is to represent it as something stable. It’s always political, it’s always unstable; it’s always a crucible for both transformation and conflict. I don’t think you can have social change movements without it, because it’s so powerful. But anytime someone starts talking about the universal power of music to unite people, be suspicious. It’s like any communal practice: the dangers of exclusion and boundary policing are always there.

“But anytime someone starts talking about the universal power of music to unite people, be suspicious.” – SK

Do hymns have a special place in the hearts of Mennonites that gives them social change power?

Pax Ressler: For many Mennonites, singing hymns may be their most visceral way of expressing and voicing faith out loud—it’s a form of prayer. As we include more social justice-oriented hymns in our hymnal supplements, the tenor of our prayers—that is, the messages we embody through our singing—have also changed. I believe that: the songs we allow to live in our bodies have the power to transform us, enabling us to embody the messages in the songs themselves as tenets of our faith.

“The songs we allow to live in our bodies have the power to transform us.” – PR

Appendix: A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel

Switzer: What do you know about the beginnings of the movement for inclusion in the Mennonite church? Were there notable moments of its origin? Specific actions that might mark its beginning?

Krehbiel: The most notable moment in the Mennonite movement for inclusion is probably the founding of Brethren Mennonite Council on LGBT Interests in 1976, by Martin Rock. (Back then it was “Gay and Lesbian Concerns.”) And that should be noted more broadly as an Anabaptist moment, since from the beginning it was ecumenical, with Brethren and Mennonites working together. Martin Rock was a gay man living in Washington, D. C. and he was fired from his position at Mennonite Central Committee for being gay after someone anonymously outed him. He had worked for them for 11 years. He started BMC around the same time that he was fired, with a group of gay Mennonite and Brethren men in the D.C. area. That organization grew (and diversified, at least in terms of gender), pretty steadily throughout the 1980s and 90s, and it continues to grow through its Supportive Communities Network.

Switzer: What have been the key moments/players in the church’s history with respect to LGBTQ+ inclusion?

Krehbiel: That’s a pretty hard question to answer because in a 40-year history, there have been a lot. BMC has been the central locus of LGBTQ Mennonite organizing for most of that history. In terms of what has happened within the institutional church—the (Old) Mennonite Church, the General Conference Mennonite Church, and eventually MCUSA—I’d say that very generally, the 1980s were marked by some gradual steps towards collective education (with many, many setbacks), the 1990s were a time of conservative retrenchment, and the MCUSA has been quite aggressively divided on LGBTQ inclusion from its inception. The MCUSA was essentially founded on a pact with conservative churches that openness towards LGBTQ inclusion would not be tolerated (see the 2001 Membership Guidelines). Conservatives interpreted that as law; moderates interpreted it as an “issue” that they hoped would become less consequential in time. LGBTQ Mennonites and those who supported them unconditionally were almost completely marginalized in the denomination’s founding. So the formation of MCUSA in 2001-2002 is certainly a key moment, and Mennonites are still living with the consequences of that.

It’s also important to remember that before MCUSA, the General Conference was certainly the more tolerant of the two denominations in terms of maintaining a congregational polity approach to churches that had LGBTQ members. That doesn’t mean there weren’t very homophobic voices within the denomination; it just means that GCs were less likely to expel congregations over LGBTQ members. The Old Mennonite Church had more of a bishop tradition as well as a stronger evangelical influence. Because so much of the General Conference was in Canada, the national split led to considerably fewer GC congregations than MC congregations in the new MCUSA. That has certainly had an effect on denominational politics.

The network of straight pastors who perform same-sex weddings has been increasingly active throughout the existence of MCUSA, particularly as queer couples have had more and more access to legal marriage. Jennifer Yoder and Luke Yoder formed Pink Menno in 2009 to be a visible queer presence at biennial MCUSA conventions and they have been the public face of the movement ever since.

In the next “How can I keep from singing?” post:

- singing in response to power

- singing and “unity”

- music and social justice movement strategy