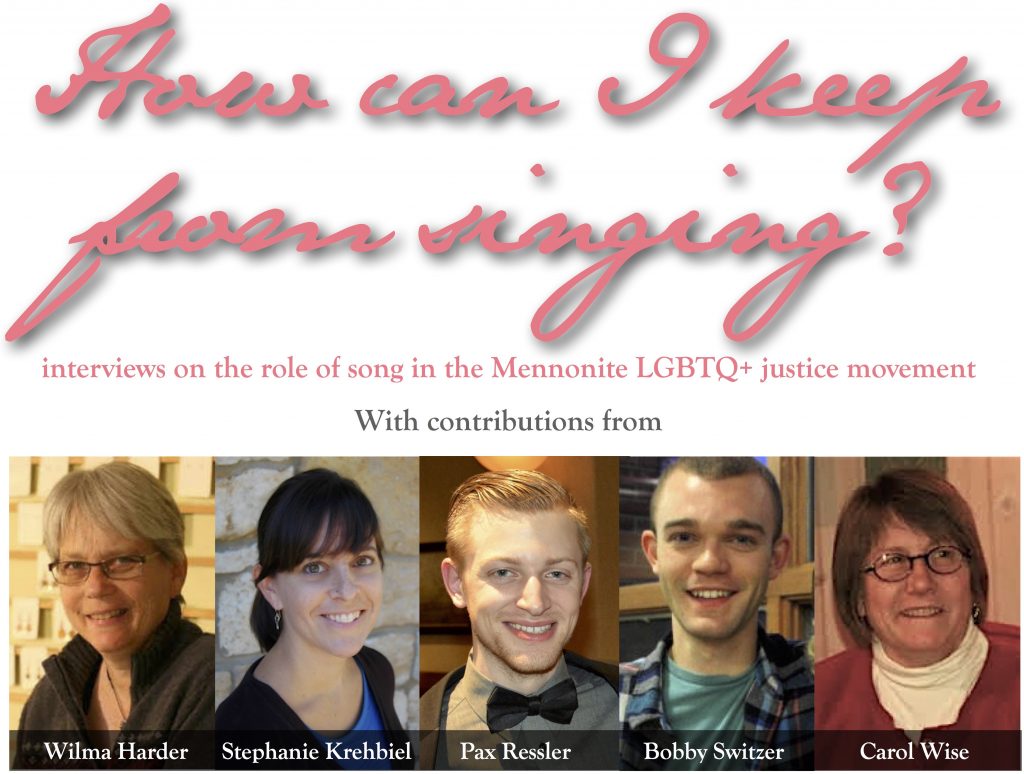

This series of posts shares interviews conducted by Bobby Switzer for a thesis project at Goshen College, curated for this series by Pax Ressler. The questions below are Bobby’s, with responses from Wilma Harder, Stephanie Krehbiel, Pax Ressler and Carol Wise. For more information about the Mennonite LGBTQ+ justice movement, see the appendix at the bottom of the page:

“A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel”.

Bobby Switzer: What songs have sustained you? Sustained the movement?

Wilma Harder: The “new” hymnal was published in 1992, amid a lot of all of this. This brought new songs into the works as well, and a new excitement of others who spoke of inclusion of all believers. Much of the songs that came back over and over at the above mentioned events were new songs filled with hope. “Here in this place” was one such song. “Will you let me be your servant” was sung so much that it became almost irrelevant. The same with “Come to the Water”.

Songs like “Unity” had been in the public domain during the 70s and brought poignantly out at opportune times over and over and over. The same with “We Shall Overcome”, of course, used so much in the 60s during the civil rights movement, and we sang it as well. I remember trying to sing that song at a BMC convention in Philadelphia, stopping part way through and thinking “you know what? I really don’t see a time when we shall overcome”. I don’t think I’ve been able to sing it through since. I think that was in 1990.

The same with “How can I keep from singing”, another song of hope and strength. In 1995 I was no longer able to sing those words, as I felt so beaten down and utterly discouraged. I could no longer sing hymns at all. I had quit attending church and had revoked my membership at Assembly. At the time I was actively performing locally with my partner and we were asked to perform at Mennofolk, and if we did so, we were to perform our version of that particular song. Well, I said, I have not been able to sing that song for a few years, and if I do so I’ll need to write some additional verses. I framed my two verses with two other verses I found in Rise Up Singing, not the hymnal.

Here are my verses:

My life goes on in endless song

my peers and loved ones question

They argue whether I belong

within the church , their bastion.

The storms that shake my inmost calm

have quenched my hope, I’m clinging

to those who love without regret.

I rarely feel like singing

Through all the tumult and the strife

I hear that music ringing.

But when I try to join right in

I feel the tears, a-stinging.

The well of sorrow deep inside

grows ever, ever deeper.

When my church to me was denied

it nearly stopped my singing.

Not the best writing, but it said then what I needed to say. I somehow got through it, and there was not a dry eye in the room.

“I somehow got through it, and there was not a dry eye in the room.” – WH

Pax Ressler: Some of Pink Menno’s anthems have become “You’ve got a place at the welcome table” and “Rain down”. Some of my best memories from the 2013 Phoenix Convention are from singing songs that don’t necessarily speak to queer inclusivity per se, but rather empower queer people to “be church” and encouragement to one another. My most powerful memory from Phoenix is holding hands in a circle of pink outside the delegate session, singing “Peace before us”. This is the church I want to be a part of.

Stephanie Krehbiel: I don’t go to church. So on a regular basis, no, it hasn’t. I listen to tons of music, but don’t participate in any kind of regular singing. That said, because I grew up in a Mennonite church with a really powerful, conventional four-part singing tradition (with an organ—I was GC), that kind of singing does have a powerful effect on me. Singing with Pink Menno has helped me get through two MCUSA conventions (Pittsburgh and Phoenix), both of which I attended for research purposes and found quite emotionally challenging. There are always a lot of tears at Pink Menno hymn sings; I was not alone in that.

I’m trying to remember songs that are consistent fixtures in Pink Menno. “What is this place,” and “My life flows on” are two that spring to mind right now. Importantly, neither of them is particularly heavy-handed with the patriarchy.

Carol Wise: In the 90’s, there was a series of conferences sponsored by BMC referred to as the “Dancing Conferences.” These conferences were held at various places in the US and were important in bringing together lgbtq people and allies. Worship and music were important components of these conferences. Jane Ramseyer Miller (who has directed “One Voice Mixed Chorus” here in Minneapolis for 20 years) even wrote “Dancing at the Wall” for one of these conferences. I’ve attached a scanned copy of it. Within the Church of the Brethren, songwriter Lee Kranbuhl wrote a very catchy piece called “We Are Not Going Away” that energized many people and was often sung.

Are there new songs that are pushing social progress/LGBTQ+ justice?

Carol Wise: In my ecumenical work, I am aware of the plethora of new hymns that are being written for the welcoming movement. Most of these are outside of the Mennonite tradition, but represent some exciting work. David Lohman, Faith Work Coordinator at the National LGBTQ Task Force, is also a talented musician and is busy putting together a hymnal for the welcoming movement. You might be interested in talking with him—he has written several wonderful pieces for the faith-based lgbtq movement.

Pax Ressler: Hymns speaking to the central focus of the current queer/transgender movement—”intersectionality” (a term that acknowledges systems of oppression such as racism, classism, sexism, cissexism, and heterosexism as connected and interrelated)—are few and far between. I recently wrote a hymn about intersectionality that was selected as a winner of Mountain States Mennonite Conference’s Anabaptist Songwriting Competition, entitled “Camina Conmigo (Walk With Me)”. I wrote this song in part to dispel the dangerous myth in many Mennonite communities that Latino and LGBTQ+ people can’t coexist and “be church” to one another due to theological differences. This is problematic on many levels—and I wanted to write a hymn that gave voice to these communities’ struggles as connected and interrelated. I think it may be one of the first of its kind in the Mennonite Church!

Are there hymns that have been detrimental to you or the movement?

Wilma Harder: Oh Bobby. My answer definitely is yes. More than I consciously know. Many times I still am not able to finish singing a particular song, as such deep feelings of hurt come to the surface. Even though Assembly is now a (mostly) completely safe space for me, there was a time when it wasn’t. Although I knew at the time that I was being damaged, I had no idea just how damaged I was becoming, or how deeply that damage was imbedded. This often happens just out of the blue when we’ll start in with a song and suddenly I just can’t sing. “How can I keep from Singing”, ironically, is one of those songs.

“Many times I still am not able to finish singing a particular song, as such deep feelings of hurt come to the surface.” – WH

Pax Ressler: I think many of the hymns that may have felt empowering to the movement at one time have outlived their usefulness to me personally in my current reality. For example, using “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy” as a hymn to advocate for LBGTQ+ justice can easily be interpreted as a call to enact radical love that overlooks sin (like the inherent “sins” of LGBTQ+ people). That message doesn’t resonate with me. It doesn’t take a radical act of love or mercy in order to accept LGBTQ+ people, just an act of human decency. LGBTQ+ people are already known and loved by God—and they are worthy to be full members of the Church. “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy” is a good hymn for everyone to use and sing in other contexts (we should be reminded that God’s mercy is wide daily), but not as a justification for extending mercy and inclusion to LGBTQ+ people. This framework denies the inherent worthiness of LGBTQ+ people, a message that can have dangerous effects on queer and transgender communities.

“It doesn’t take a radical act of love or mercy in order to accept LGBTQ+ people, just an act of human decency.” – PR

Are you aware of any stories about hymn singing causing a shift in one’s beliefs in regards to LGBTQ+ justice?

Stephanie Krehbiel: No, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t any. I think it’s probable that Pink Menno’s presence has forced some people to confront their discomfort with being in proximity to openly queer bodies. I would imagine that there are a lot of untold stories of personal transformation there—both from straight folks and from LGBTQ folks who have been able to be more comfortable with themselves.

Pax Ressler: The measurable social impact of singing hymns (as it related to “changing hearts and minds”) is hard to define—and likely less important than empowering queer/transgender people with the knowledge that they belong, that they are valuable and that they are loved. As with most forms of social advocacy, people change as a result of people; people change from having a specific, important personal connection to LGBTQ+ justice. I imagine that many who do not have this connection or have chosen to shun/silence their queer/transgender loved ones see Pink Menno hymn sings as self-righteous and inappropriate. This line of thought is a distinct position of privilege in not having the need to advocate for themselves and their community in Mennonite spaces. LGBTQ+ people live in daily need of advocacy and empowerment in the Mennonite Church—a reality that many do not realize or understand.

What hymns are important to you? Are there specific lyrics?

Pax Ressler: The songs I chose for the “Stand By Me: Hymns of Hope & Healing” album (a response to violence against queer/transgender people in the Mennonite Church) have significant meaning for me. This visual imagery for healing speaks to me:

Let the seed of freedom awake and flourish

Let the deep roots nourish, let the tall stalks rise

O healing river, send down your waters

O healing river, from out of the skies

Like many others, I live for:

The sure provisions of my God attend me all my days

O may thy house be mine abode and all my works be praise

There would I find a settled rest while others go and come

No more a stranger, nor a guest, but like a child at home

This feels incredibly relevant in thinking about the many LGBTQ+ people who have been exiled or have been forced to leave the Church for their own safety (and were brave enough to seek health and wholeness elsewhere). To these people, I imagine “No more a stranger, nor a guest, but like a child at home” is one of the most beautiful images for God’s love.

Appendix: A History Lesson with Dr. Krehbiel

Switzer: What do you know about the beginnings of the movement for inclusion in the Mennonite church? Were there notable moments of its origin? Specific actions that might mark its beginning?

Krehbiel: The most notable moment in the Mennonite movement for inclusion is probably the founding of Brethren Mennonite Council on LGBT Interests in 1976, by Martin Rock. (Back then it was “Gay and Lesbian Concerns.”) And that should be noted more broadly as an Anabaptist moment, since from the beginning it was ecumenical, with Brethren and Mennonites working together. Martin Rock was a gay man living in Washington, D. C. and he was fired from his position at Mennonite Central Committee for being gay after someone anonymously outed him. He had worked for them for 11 years. He started BMC around the same time that he was fired, with a group of gay Mennonite and Brethren men in the D.C. area. That organization grew (and diversified, at least in terms of gender), pretty steadily throughout the 1980s and 90s, and it continues to grow through its Supportive Communities Network.

Switzer: What have been the key moments/players in the church’s history with respect to LGBTQ+ inclusion?

Krehbiel: That’s a pretty hard question to answer because in a 40-year history, there have been a lot. BMC has been the central locus of LGBTQ Mennonite organizing for most of that history. In terms of what has happened within the institutional church—the (Old) Mennonite Church, the General Conference Mennonite Church, and eventually MCUSA—I’d say that very generally, the 1980s were marked by some gradual steps towards collective education (with many, many setbacks), the 1990s were a time of conservative retrenchment, and the MCUSA has been quite aggressively divided on LGBTQ inclusion from its inception. The MCUSA was essentially founded on a pact with conservative churches that openness towards LGBTQ inclusion would not be tolerated (see the 2001 Membership Guidelines). Conservatives interpreted that as law; moderates interpreted it as an “issue” that they hoped would become less consequential in time. LGBTQ Mennonites and those who supported them unconditionally were almost completely marginalized in the denomination’s founding. So the formation of MCUSA in 2001-2002 is certainly a key moment, and Mennonites are still living with the consequences of that.

It’s also important to remember that before MCUSA, the General Conference was certainly the more tolerant of the two denominations in terms of maintaining a congregational polity approach to churches that had LGBTQ members. That doesn’t mean there weren’t very homophobic voices within the denomination; it just means that GCs were less likely to expel congregations over LGBTQ members. The Old Mennonite Church had more of a bishop tradition as well as a stronger evangelical influence. Because so much of the General Conference was in Canada, the national split led to considerably fewer GC congregations than MC congregations in the new MCUSA. That has certainly had an effect on denominational politics.

The network of straight pastors who perform same-sex weddings has been increasingly active throughout the existence of MCUSA, particularly as queer couples have had more and more access to legal marriage. Jennifer Yoder and Luke Yoder formed Pink Menno in 2009 to be a visible queer presence at biennial MCUSA conventions and they have been the public face of the movement ever since.

Dear Friends, thank you for this. ‘How can I keep from singing/’ is a favourite in our church – St. David’s Uniting Church, Pontypridd, South Wales (UK) We are a progressive and inclusive church of Baptists, United Reformed, Presbyterians and others.

You may not have heard of me yet. (You have now) I am responsible for the 21st century/women friendly/gay friendly/ sinner friendly/ non religious and non-academic friendly ‘GOOD AS NEW’ – A Radical Re-telling of the Christian Scriptures.

ALSO ‘Wide Awake Worship’ – traditional hymns and prayers updated for the 21st century.

If you will give me a forwarding address, I will send you a copy of both of these books. I know that you will be impressed. Love & Peace to you all, John Henson.

Thanks for this read…so frequently I/we sing without care for the words we warble, but just as frequently I shed tears for our lack of inclusive language, actions, and thoughts. Thx for your work!